Introduction

The demographic dividend is commonly defined as the accelerated economic growth that can occur as a population age structure matures. This web feature expands the concept of the demographic dividend to four potential sets of benefits, or dividends. In addition to economic growth, it outlines benefits in health, education, and governance and stability.

Among countries with youthful populations, advancing to a more mature age structure increases the likelihood of achieving substantial gains in each of these four sectors. This web feature explains how reaching multiple important benchmarks under each dividend becomes more attainable as countries progress through the demographic transition—the shift from high to low fertility and mortality, which leads to a higher share of the population in the working ages.

As a country’s population matures and reaches specific age-structure thresholds, it becomes more likely than not to achieve the benchmarks under each dividend. When the median ageThe age that divides a population into two numerically equal groups where half the people are younger than this age and half are older. of the population is between 26 and 40 years, countries enter a demographic window of opportunity to achieve accelerated economic growth and benefits across a range of development sectors. If government policies enhance job opportunities for the working-age population, countries are likely to experience improvements in many measures of sustainable development USAID Country Roadmap Portal during this window. However, countries with youthful age structures typically have greater difficulty achieving progress on those measures.

With a better understanding of the potential benefits of age structure change across key sectors, advocates and policymakers can generate multisectoral commitment to investments in voluntary family planning and girls’ education in their country. This analysis illustrates both the current status of progress in key sectors: health, education, economy, and governance, as well as projections for the likelihood of future achievement of benchmarks in these sectors based on age structure change.

Health Dividend

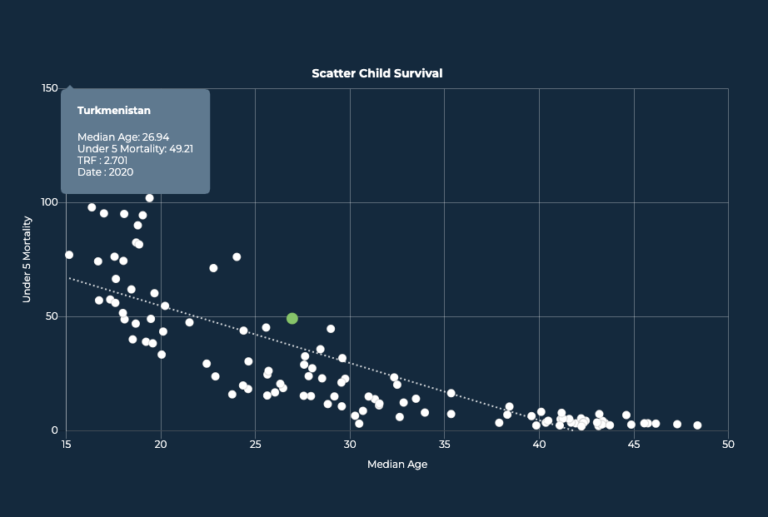

Maternal and child mortality are core indicators of health and well-being. Despite remarkable improvements in maternal and child health over the last three decades, many pregnant women and children under age 5 die every year of preventable causes.

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 3 aims to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.” The first two targets of this goal focus on improving maternal and child health, including:

- Target 3.1: By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 deaths per 100,000 live births.

- Target 3.2: By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 deaths per 1,000 live births.

In addition to the catastrophic social and emotional costs, maternal deaths result in significant losses in socioeconomic development. When maternal and child health improve, families, communities, and countries experience multigenerational health and economic benefits. Voluntary family planning services improve maternal and child survival by providing women with the means and information to avoid high-risk pregnancies. Research finds that access to and use of family planning can reduce maternal mortality by 30 percent or more.

Extending the interval between births also improves outcomes for child health and nutrition. In addition, uptake of family planning reduces early childbearing, which is associated with poor health and educational outcomes for children. In turn, improvements in child survival affect preferences about family size. Studies suggest that couples choose to have smaller families when they know that each child has a better chance of surviving. With fewer children to support, parents are better able to invest in their children’s health, education, and well-being.

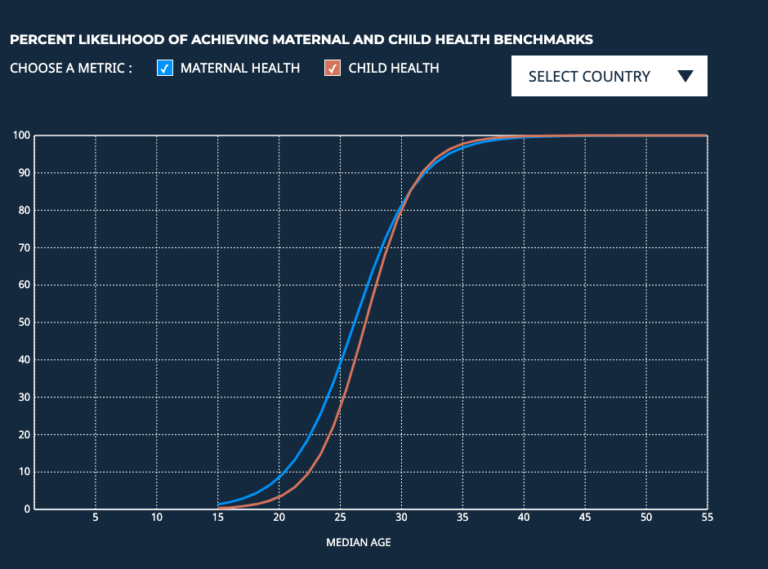

As women and couples are better able to plan whether, when, and how often to have children, countries tend to transition from high to low fertility and child mortality. As fertility declines and age structure changes, countries become more likely to achieve the health dividend, measured by two key benchmarks for improvements in maternal and child health:

- A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the maternal health benchmark, measured by a reduction in the maternal mortality ratio to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, when the median age of the population reaches 26 years.

- A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the child health benchmark, measured by a mortality rate of children under age 5 less than or equal to 25 deaths per 1,000 live births, when the median age of the population reaches 27 years.

Learn more about the relationship between population age structure across countries through the interactive charts below. Start by exploring a country’s likelihood of achieving the health dividend benchmarks.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the maternal health benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 26 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the child health benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 27 years.

EXPLORE HEALTH DATA

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Health Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Maternal health

- Child health

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Maternal And Child Health Metrics By Country And Median Age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Health Benchmarks

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Health Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Maternal health

- Child health

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

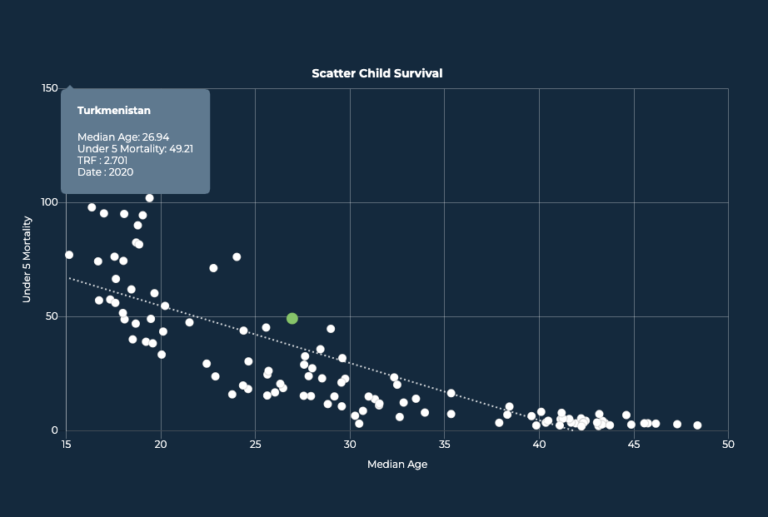

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

Maternal And Child Health Metrics By Country And Median Age

Maternal And Child Health Metrics By Country And Median Age

- Choose a metric :

- Child health

- Maternal health

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

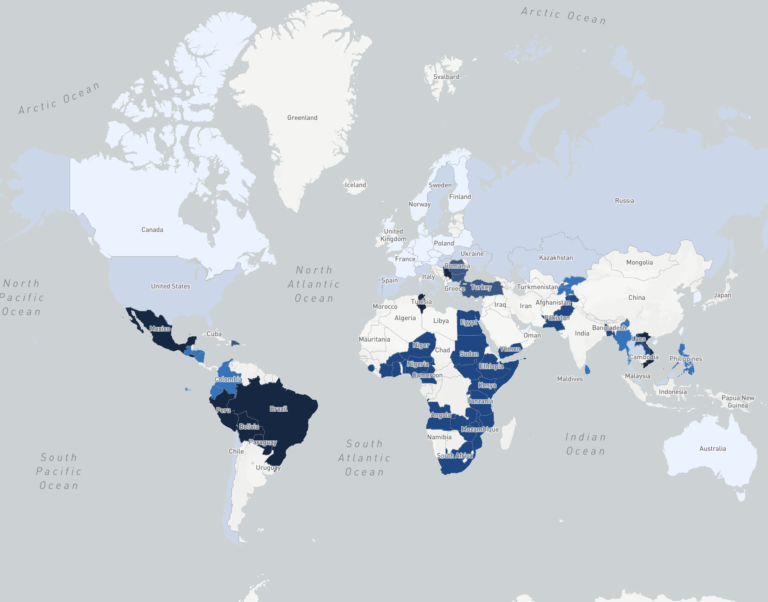

Geographic Distribution of Health Metrics

Geographic Distribution of Health Metrics

- Choose a metric :

- Child health

- Maternal health

Under-5 mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births)

-

< 5

-

5 – 9

-

10 – 24

-

25 – 49

-

> 50

-

No Data

Under-5 mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births)

-

< 5

-

5 – 9

-

10 – 24

-

25 – 49

-

> 50

-

No Data

Maternal mortality ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births)

-

< 25

-

25 – 69

-

70 – 199

-

200 – 499

-

> 500

-

No Data

Maternal mortality ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births)

-

< 25

-

25 – 69

-

70 – 199

-

200 – 499

-

> 500

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Education Dividend

Education is one of the most powerful and proven vehicles for sustainable development and is central to realizing the Sustainable Development Goals.

When both boys and girls have access to education, accelerated economic growth is possible. Secondary education—especially for girls—helps delay marriage and first pregnancy. Women with higher levels of education are also more likely to work outside the home—increasing the size of the wage-earning labor force and the potential for economic development.

Improving secondary school enrollment gives young people the skills to join a competitive global workforce and accelerates progress toward the educational attainment dividend.

- A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve late secondary school enrollment rates at or above 60 percent when the median age of the population reaches 24 years.

- Advancing to high levels of educational attainment becomes likely later in the age-structure transition: A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve late secondary attainment rates at or above 60 percent among young adults at a median age of 30 years.

Learn more about the relationship between population age structure across countries through the interactive charts below. Start by exploring a country’s likelihood of achieving the education dividend benchmarks.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the late secondary school enrollment benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 24 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the late secondary attainment benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 30 years.

EXPLORE EDUCATION DATA

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Education Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Late secondary educational attainment

- Late secondary enrollment

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Education Metrics By Country And Median Age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Education Benchmarks

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Education Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Late secondary educational attainment

- Late secondary enrollment

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

Education Metrics By Country And Median Age

Education Metrics By Country And Median Age

- Choose a metric :

- Late secondary enrollment

- Late secondary educational attainment

Note

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Geographic Distribution of Education Metrics

Geographic Distribution of Education Metrics

- Choose a metric :

- Late secondary educational attainment

- Late secondary enrollment

Percent with educational attainment of late secondary education or higher (ages 20-29)

-

< 25

-

25 – 59

-

60 – 79

-

> 80

-

No Data

Percent with educational attainment of late secondary education or higher (ages 20-29)

-

< 25

-

25 – 59

-

60 – 79

-

> 80

-

No Data

Gross enrollment ratio in late secondary education or higher (ages 20-29)

-

< 30

-

30 – 59

-

60 – 89

-

90 – 119

-

> 120

-

No Data

Gross enrollment ratio in late secondary education or higher (ages 20-29)

-

< 30

-

30 – 59

-

60 – 89

-

90 – 119

-

> 120

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

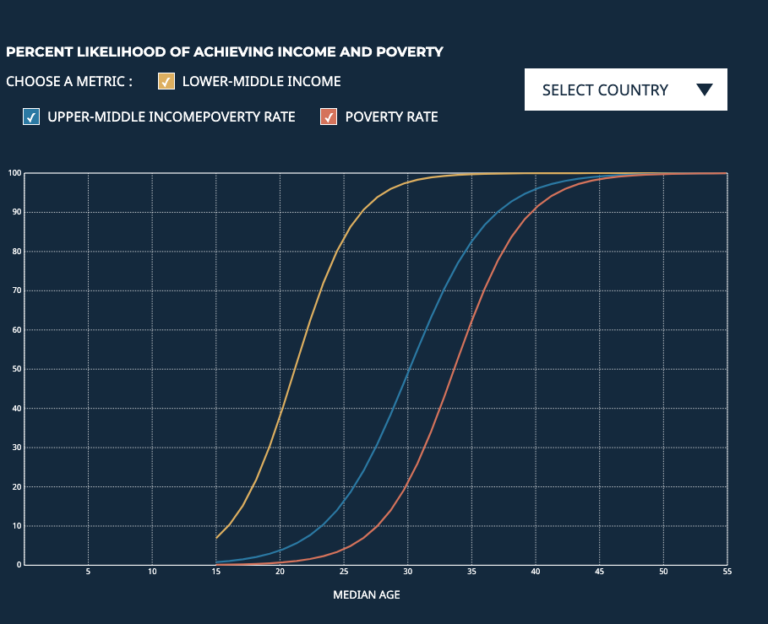

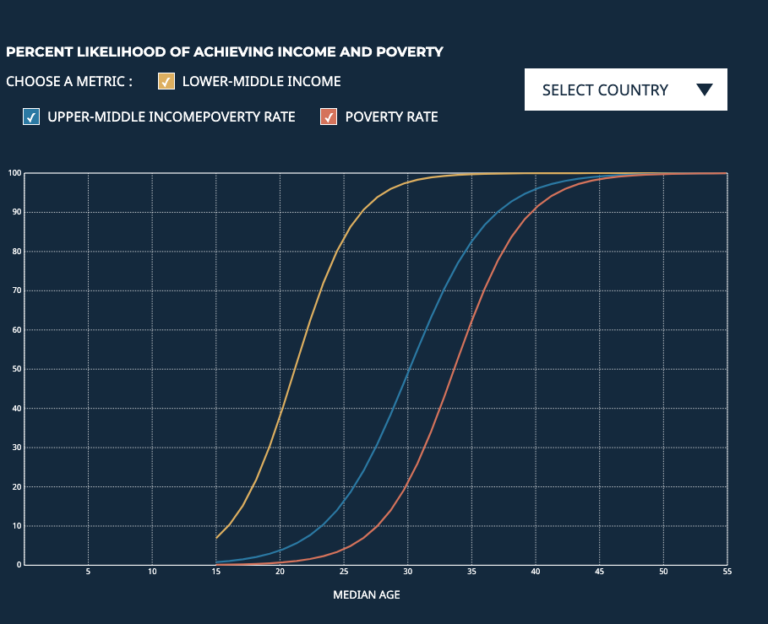

Economy Dividend

A healthy and educated population generates a productive labor force that contributes directly to increased wealth and poverty reduction, improving income per capita and promoting economic transformation.

Sound economic policies that attract foreign investment, grow the manufacturing and service sectors, and meet the employment needs of a growing labor force, provide a solid foundation for rapid economic growth. When the ratio of the working-age population to the nonworking-age population increases and is coupled with strategic investments that stimulate the economy, countries are increasingly likely to earn upper-middle income status. The transition in a country’s age structure can also facilitate a decline in the share of the population living in poverty.

- Although countries may reach lower-middle income status, based on GNI (or gross national income), early in the age-structure transition, the benchmark of attaining upper-middle income status becomes more than 50 percent likely much later in the age-structure transition at a median age of 30 years.

- Achievement of a low poverty rate occurs later in the transition. A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the poverty reduction benchmark―defined as a poverty rate of 12 percent or fewer of the population living on less than $5.00 per day―when the median age of the population reaches 34 years.

Structural shifts in the economy from low- to high-productivity employment—typically from agriculture (primarily subsistence agriculture) to industry and services and from informal to formal employment—can drive economic development. Changes in population age structure can facilitate this shift towards a more productive and competitive labor force.

As median age increases and households are better able to invest in the health and education of each child, the human capital of the future workforce grows. This accumulation of human capital can accelerate the shift to an economy in which employment is increasingly concentrated in higher-income jobs in industry, services, or technology, rather than agriculture.

Population age structure change and the corresponding improvements in human capital can also lead to a more equal share of men and women participating in the workforce, a concept known as economic gender parity. As fertility declines, more women have the opportunity to stay in school, build skills for the formal labor market, and increase their earnings.

Both the structural shift in the economy and increased female participation in the workforce can contribute to increases in income and rapid economic growth.

- A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the economic transformation benchmark—defined as an employment threshold with 20 percent or fewer of the population employed in agriculture—when the median age of the population reaches 30 years.

- A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the economic gender parity benchmark—defined as having at least 9 women for every 10 men in the professional workforce (a ratio of 0.9 or higher)—when the median age of the population reaches 32 years.

Learn more about the relationship between population age structure across countries through the interactive charts below. Start by exploring a country’s likelihood of achieving the economy dividend benchmarks.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the upper-middle income status benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 30 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the poverty reduction benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 34 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the economic transformation benchmark—defined as an employment threshold with 20 percent or fewer of the population employed in agriculture—when the median age of the population reaches 30 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the economic gender parity benchmark—defined as having at least 9 women for every 10 men in the professional workforce (a ratio of 0.9 or higher)—when the median age of the population reaches 32 years.

Explore Economy Data

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Economic Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Lower-middle income

- Upper-middle income

- Poverty reduction

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

GNI Per Capita and Poverty Rate By Country and Median Age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Economic transformation

- Economic gender parity

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity By Country and Median Age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Economic Benchmarks

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Lower-Middle Income, Upper-Middle Income, and Poverty Reduction Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Lower-middle income

- Upper-middle income

- Poverty reduction

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

GNI Per Capita and Poverty Rate By Country and Median Age

GNI Per Capita and Poverty Rate By Country and Median Age

- Choose a metric :

- GNI per capita

- Poverty rate

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

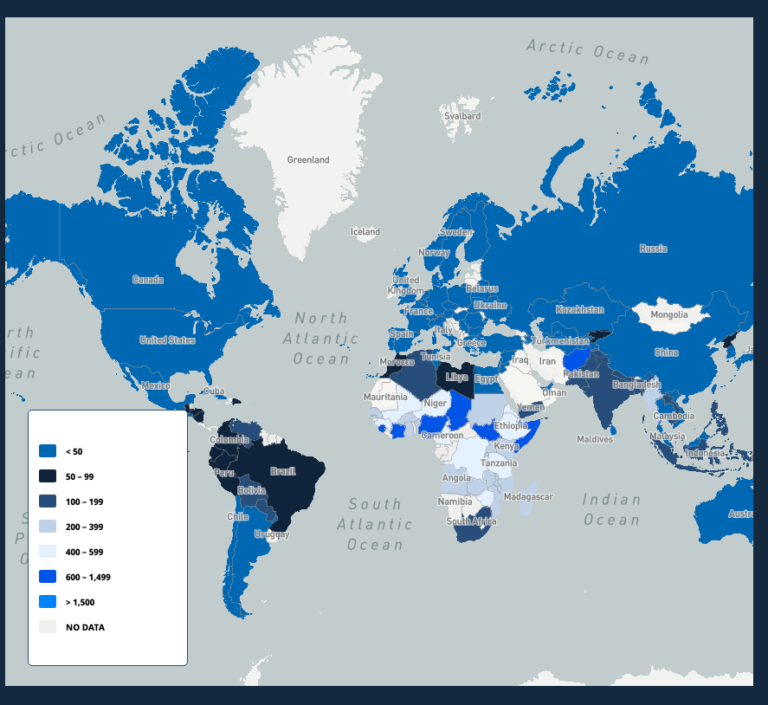

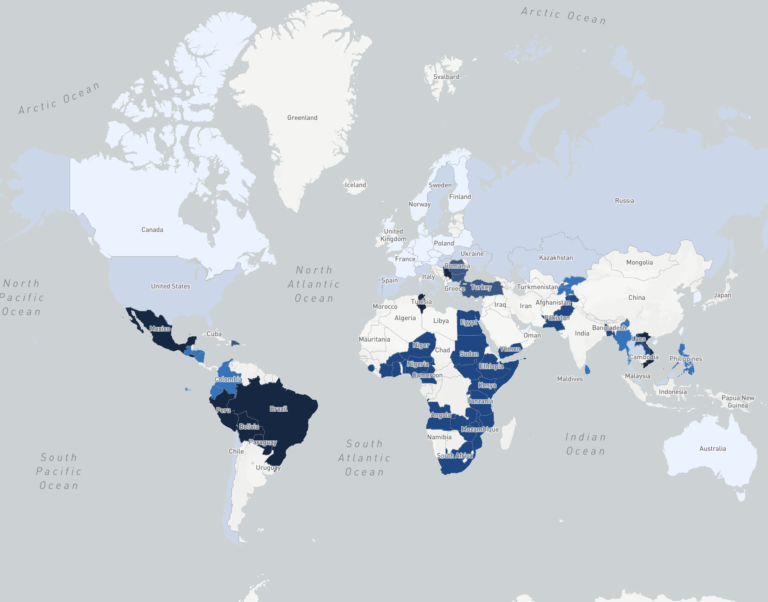

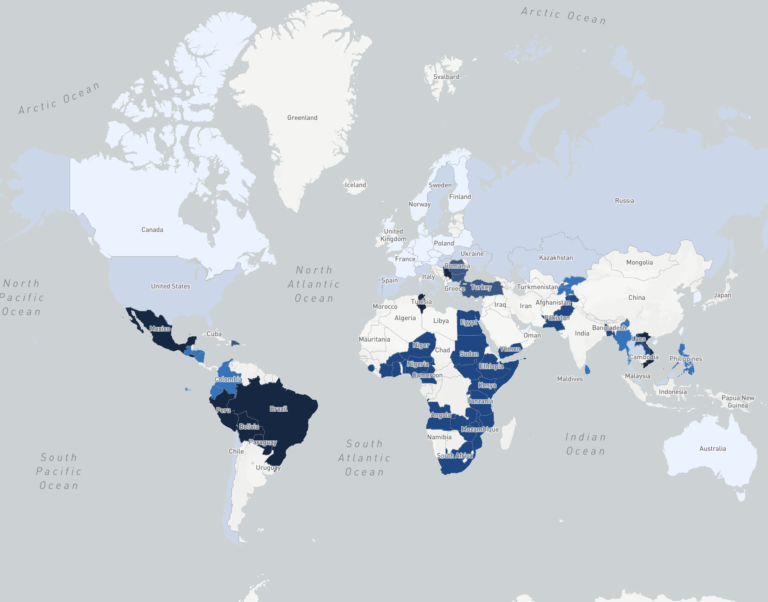

Geographic Distribution of GNI Per Capita and Poverty Rate

Geographic Distribution of GNI Per Capita and Poverty Rate

- Choose a metric :

- GNI per capita

- Poverty reduction

GNI per capita ($US, atlas method)

-

< 1,046

-

1,046 – 4,095

-

4,096 – 12,694

-

> 12,695

-

No Data

GNI per capita ($US, atlas method)

-

< 1,046

-

1,046 – 4,095

-

4,096 – 12,694

-

> 12,695

-

No Data

Percent living on less than $5.00 per day (purchasing power parity)

-

< 12

-

12 – 24

-

25 – 49

-

50 – 74

-

> 75

-

No Data

Percent living on less than $5.00 per day (purchasing power parity)

-

< 12

-

12 – 24

-

25 – 49

-

50 – 74

-

> 75

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity Benchmarks

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Economic transformation

- Economic gender parity

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity By Country and Median Age

Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity By Country and Median Age

- Choose a metric :

- Economic gender parity

- Economic transformation

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Geographic Distribution of Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity

Geographic Distribution of Economic Transformation and Economic Gender Parity

- Choose a metric :

- Economic gender parity

- Economic transformation

Female-to-male professional workforce ratio

-

< 0.50

-

0.50 – 0.89

-

0.90 – 1.49

-

> 1.50

-

No Data

Female-to-male professional workforce ratio

-

< 0.50

-

0.50 – 0.89

-

0.90 – 1.49

-

> 1.50

-

No Data

Percent of population employed in the agricultural sector

-

< 10

-

10 – 19

-

20 – 39

-

40 – 59

-

> 60

-

No Data

Percent of population employed in the agricultural sector

-

< 10

-

10 – 19

-

20 – 39

-

40 – 59

-

> 60

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

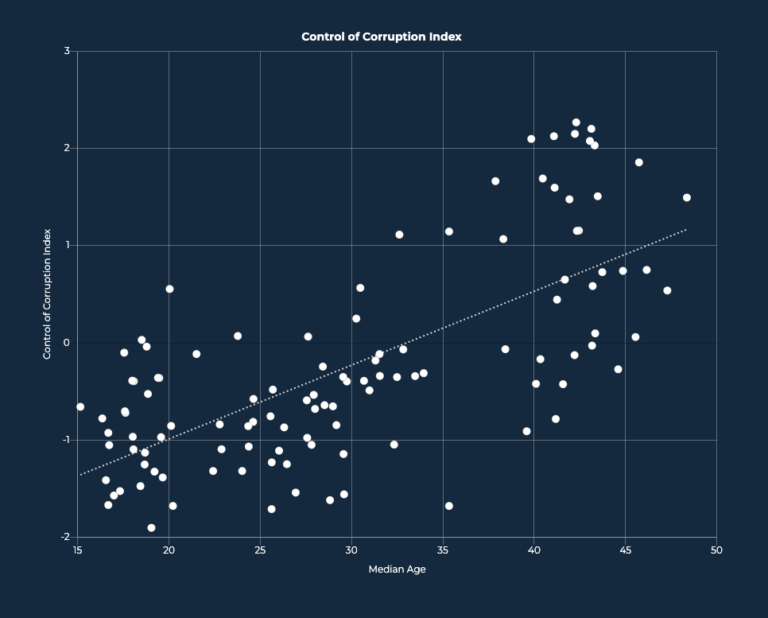

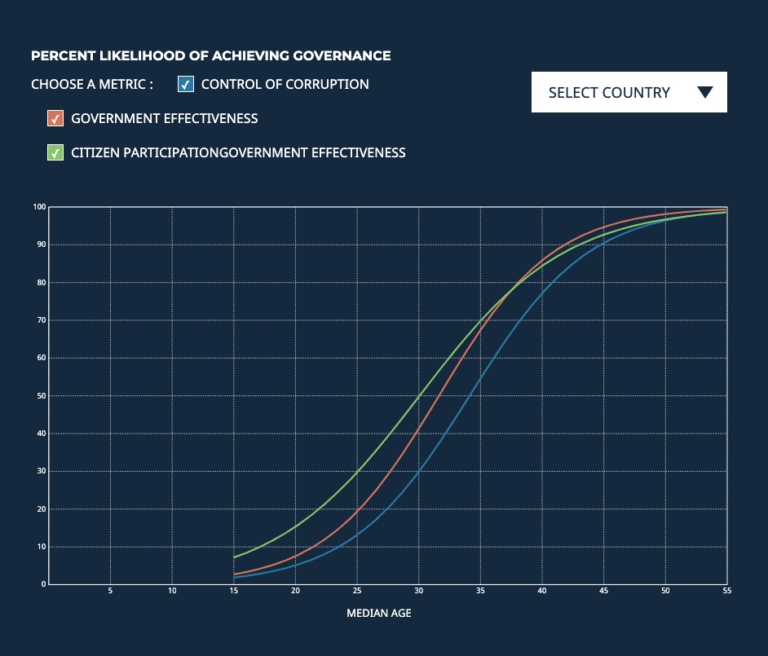

Governance Dividend

Countries with a youthful age structure are at increased risk of conflict and instability and face significant challenges building robust and effective institutions and fostering citizen participation. Sustainable Development Goal 16 aims to foster “peaceful and inclusive societies” and ensure access to “effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions.” Attaining a more mature age structure increases a country’s likelihood of effective governance and political stability.

Research suggests that declines in fertility and the resulting shifts in age structure can influence several key dimensions of governance. While the causal linkages between age structure and governance require further research, some potential pathways are explored below.

Smaller family size allows parents and governments to increase investment in health and education. A healthier and better educated population tends to contribute to more effective government institutions and services and increased civic participation.

In addition, in large youthful populations, tensions within the population, high unemployment and underemployment, and rapid rural emigration can increase the risk of violent conflict, insecurity, and corruption.

As fertility declines and median age increases, a country becomes more likely to perform above average in key measures of good governance:

- Countries become more than 50 percent likely to achieve the citizen voice and accountability (or “citizen participation”) benchmark—defined as above-average performance in citizen participation in selecting the government, freedom of expression and association, and a free media—when the median age of the population reaches 30 years.

- Countries become more than 50 percent likely to achieve the government effectiveness benchmark—defined as above-average performance in the quality of public services, the civil service, policy formulation, and policy implementation—when the median age of the population reaches 32 years.

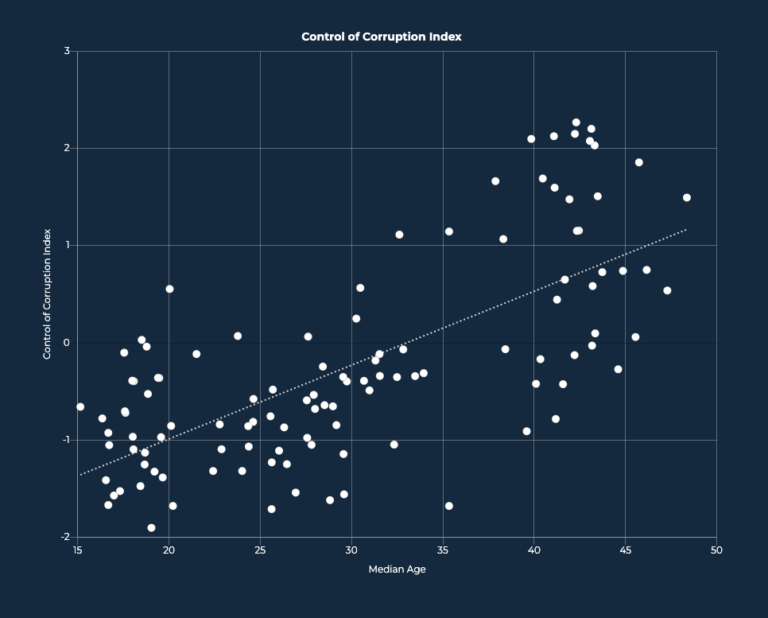

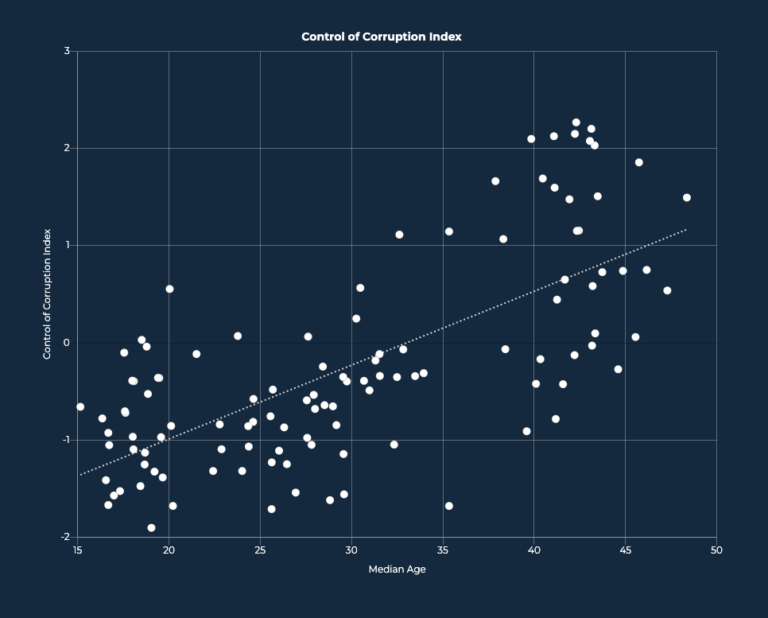

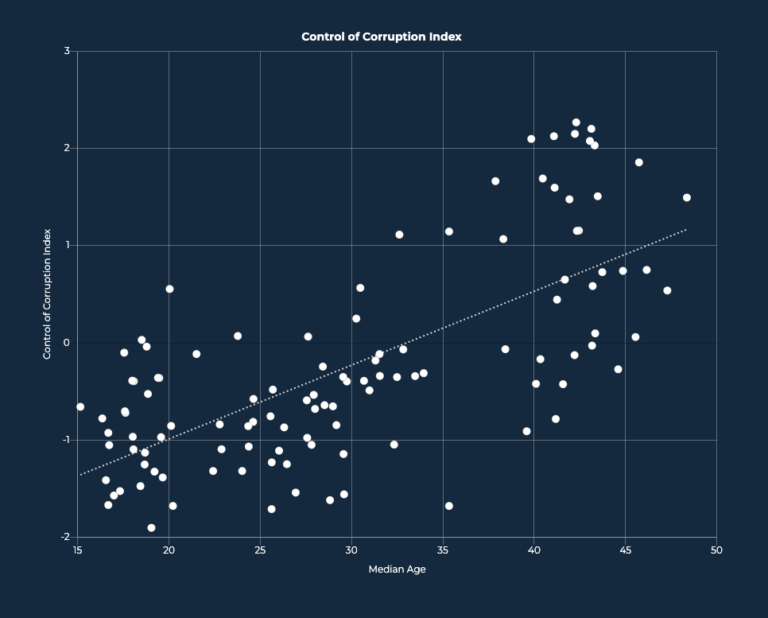

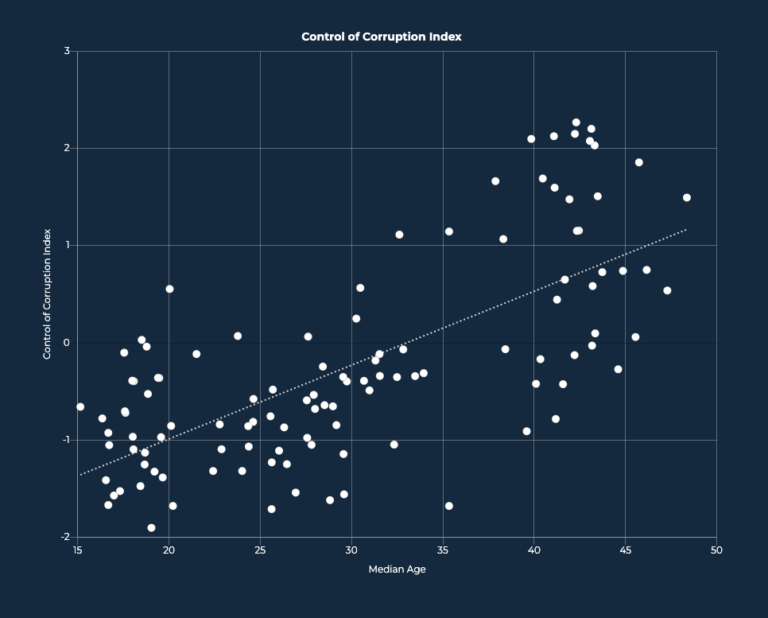

- Countries become more than 50 percent likely to achieve the control of corruption benchmark—defined as above-average performance of the state in serving public, rather than private, interests—when the median age of the population reaches 34 years.

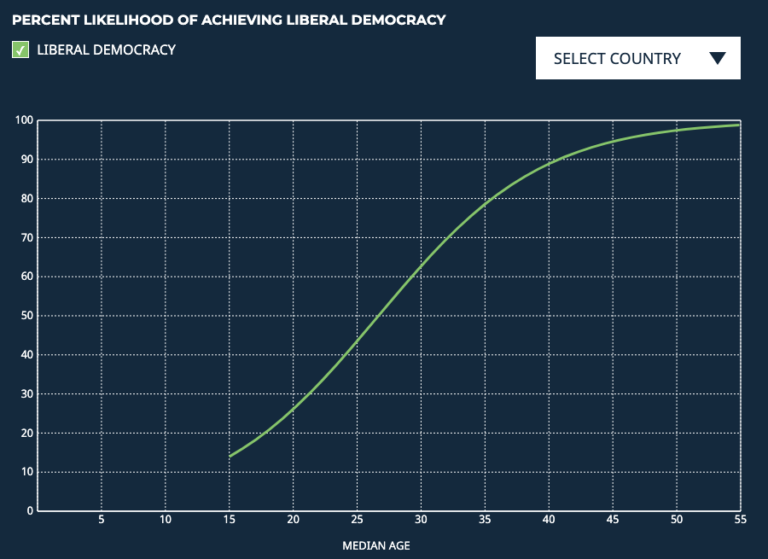

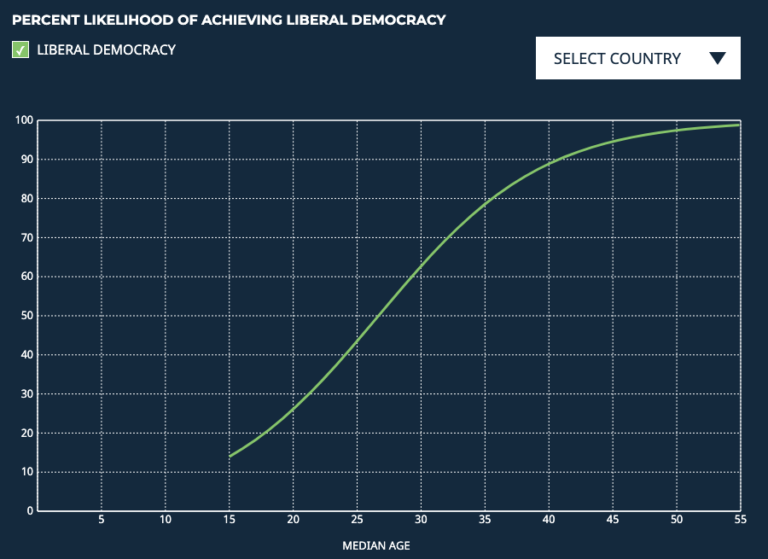

Population age structure is further associated with achieving and sustaining liberal democracy, a system of governance that comprises free and fair elections, free association and freedom of expression, equality before the law, and judicial and legislative constraints on the executive branch of government.

As the median age of the population increases, stability and economic prosperity tend to improve. These improvements can catalyze citizens’ increased political agency and participation and foster conditions conducive to democracy. Research further suggests that countries with youthful population age structures may introduce democracy or democratic reforms, but experience challenges in sustaining it.

- Countries become more than 50 percent likely to achieve the liberal democracy benchmark—defined as above-average performance on the liberal democracy index Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) is an unique approach to conceptualizing and measuring democracy.—when the median age of the population reaches 27 years.

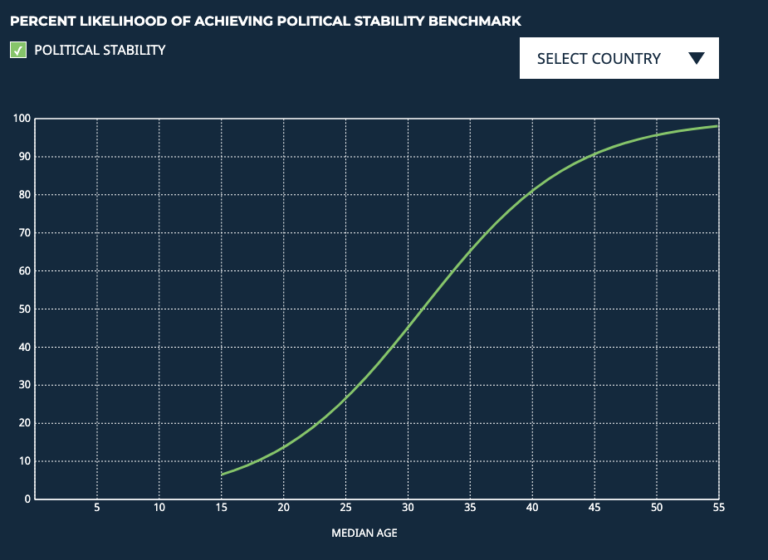

Finally, a maturing population age structure is also linked to improved political stability, including a reduced risk of politically motivated violence.

Studies show that youthful populations are more susceptible to violence and civil unrest, particularly where high rates of poverty and unemployment exist. In particular, numerous studies have concluded that countries with a youthful age structure are more likely to experience revolutionary conflict aimed at overthrowing the government.

- A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the political stability benchmark—defined as above-average performance in the risk of politically motivated violence and instability—when the median age of the population reaches 31 years.

Learn more about the relationship between population age structure across countries through the interactive charts below. Start by exploring a country’s likelihood of achieving the governance dividend benchmarks.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the citizen participation benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 30 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the government effectiveness benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 32 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the control of corruption benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 34 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the liberal democracy benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 27 years.

A country becomes more than 50 percent likely to achieve the political stability benchmark when the median age of the population reaches 31 years.

Explore Governance Data

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Governance Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Control of corruption

- Government effectiveness

- Citizen voice and accountability

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Governance Metrics by Country and Median age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Governance Benchmarks

- Political stability

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Political Stability By Country and Median Age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Liberal Democracy Benchmark

- Liberal democracy

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Liberal Democracy By Country and Median Age

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Governance Benchmarks

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Citizen Participation, Control of Corruption, and Government Effectiveness Benchmarks

- Choose a metric :

- Control of corruption

- Government effectiveness

- Citizen voice and accountability

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

Governance Metrics by Country and Median age

Citizen Participation, Control Of Corruption, and Government Effectiveness By Country and Median Age

- Choose a metric :

- Citizen participation

- Control of corruption

- Government effectiveness

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

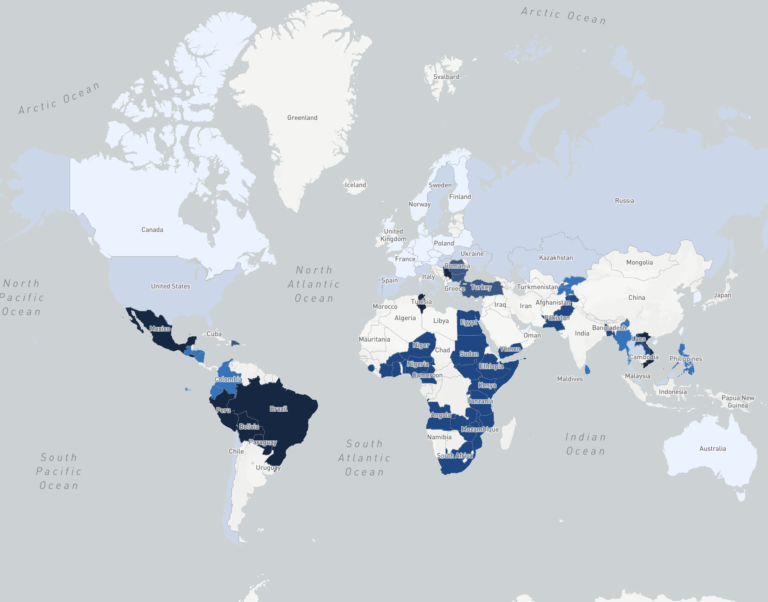

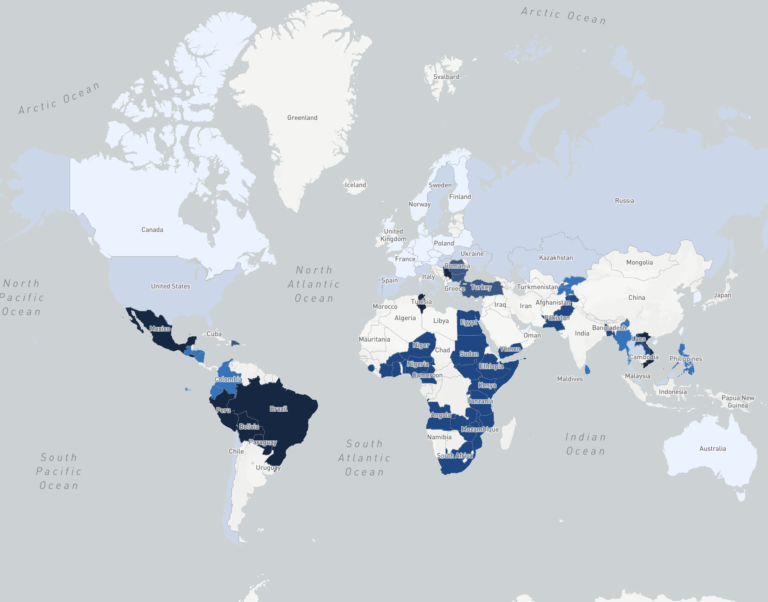

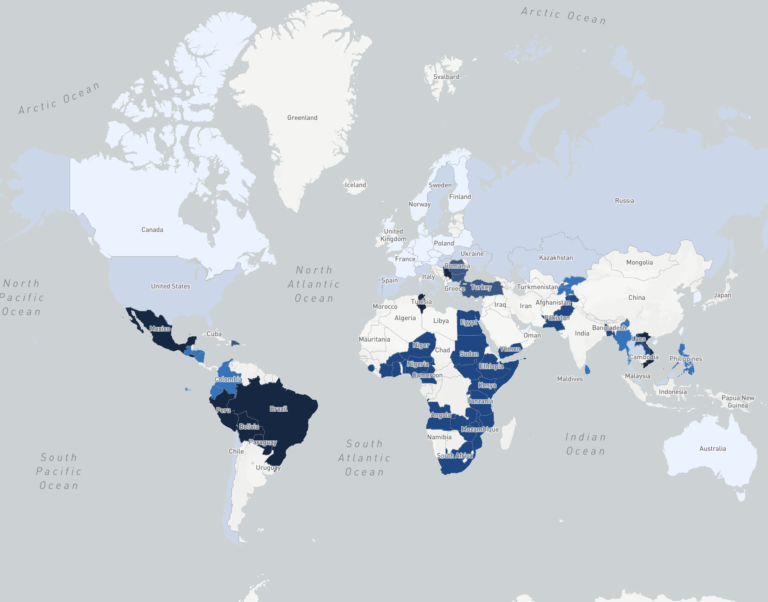

Geographic Distribution of Governance Metrics

Geographic Distribution of Citizen Participation, Control Of Corruption, and Government Effectiveness

- Choose a metric :

- Citizen participation

- Control of Corruption Index

- Government effectiveness

Citizen voice and accountability index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Citizen voice and accountability index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Control of Corruption Index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Control of Corruption Index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Government effectiveness index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Government effectiveness index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Governance Benchmarks

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Political Stability Benchmark

- Political stability

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

Political Stability By Country and Median Age

Political Stability By Country and Median Age

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Geographic Distribution of Political Stability

Geographic Distribution of Political Stability

Political stability index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Political stability index

-

< -1

-

-1- -0.1

-

0-0.9

-

1+

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Liberal Democracy Benchmark

Percent Likelihood of Achieving Liberal Democracy Benchmark

- Liberal democracy

Year:

TFR:

Median Age:

Percent Likelihood:

Instructions

Select a country from the drop-down menu.

The curved lines are based on statistical analysis of historical data from 113 countries and illustrate the probability of a country achieving each benchmark based on its median age. As fertility rates decline, median age increases, increasing the likelihood that a country will attain the benchmarks within each dividend. Hover over each point on the curve to see the year, the projected total fertility rate in that year, the projected median age of the population in that year, and the percent likelihood of achieving the benchmark based on the median age.

Liberal Democracy By Country and Median Age

Liberal Democracy By Country and Median Age

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

Geographic Distribution of Liberal Democracy

Geographic Distribution of Liberal Democracy

Liberal democracy index

-

< 0.25

-

0.25 – 0.49

-

0.50 – 0.74

-

> 0.75

-

No Data

Liberal democracy index

-

< 0.25

-

0.25 – 0.49

-

0.50 – 0.74

-

> 0.75

-

No Data

Notes

Data are latest available as of February 2022. Countries whose latest available data are more than five years older than the most recent available year for any country were excluded.

MOVING FORWARD

Progress through a demographic transition, when a country moves from high birth and death rates to lower birth and death rates, and the resulting change in population age structure is essential to achieving any of the benchmarks under each of the four dividends. Where youthful populations persist, the large size of the young population relative to the working-age population is likely to delay all four dividends.

Investment in voluntary family planning information and services supports women and girls to make informed, full, and free choices about using contraception and having children. This analysis underscores that such investment can also help countries achieve policy goals that advance the well-being of their populations for generations to come.

Methodology

Data from over 100 countries were used to convert the demographic window into an age range based on the median age of the population. The analysis excluded countries with populations of less than 5 million and those with economies dependent on oil or mineral resources. Median age data were obtained from the United Nations Population Division (UNPD)’s World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision.

Data for the four dividends were obtained from publicly available sources:

- Analysis of the health dividend used under-5 mortality data from the UNPD for the period 1970-2020 and maternal mortality ratio data from the WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank and UNPD report Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000-2017.

- Analysis of the educational enrollment dividend used late secondary enrollment data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics for the period 1981-2020.

- Analysis of the educational attainment dividend used educational attainment distribution data from Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (2018) and population estimates from UNPD’s World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision for the period 1970-2015.

- Analysis of the income per capita benchmark under the economic dividend used gross national income per capita data (Atlas Method) from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for the period 1971-2020. Analysis of the poverty rate used the World Bank’s World Development Indicators on poverty headcount with a poverty line of $5.00 per day, in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms for the period 1981-2019. Analysis of the economic transformation benchmark used data on the percent of the total population employed in agriculture from the International Labour Organization (ILO) (ILOSTAT database) for the period 1991-2020. Analysis of the economic gender gap used data on the female-to-male ratio of the professional workforce from the ILOSTAT database as featured in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap report for the period 1991-2020.

- Analysis of the governance and stability dividend used multiple data sources:

- The following indicators come from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators for the period 1996-2020:

- Government effectiveness: Perception of the quality of public services and the civil service as well as the quality of policy formulation and implementation.

- Voice and accountability: Perception of citizen participation in selecting the government, and freedom of expression and association, and a free media.

- Control of corruption: Perception of the extent to which the state services public, rather than private, interests.

- Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism: Perception of the likelihood of political instability or politically motivated violence.

- Analysis for the liberal democracy benchmark used the liberal democracy index data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project, V-Dem Institute of the University of Gothenburg for the period 1970-2020. The liberal democracy index includes two main components:

- Electoral democracy component (comprises five indices): Freedom of association, clean elections, freedom of expression and alternative sources of information, elected officials, and suffrage.

- Liberal democracy (comprises three components): Equality before the law and individual rights, judicial constraints on the executive branch, and legislative constraints on the branch.

- The following indicators come from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators for the period 1996-2020:

Multivariate logistic regression analyses generated full and partial logistic functions for each dividend. Statistical analysis measured the effect of age structure on each single benchmark including the controls described above and did not directly measure any potential feedback loops between dividends or from dividends to age structure.

The data used in the four dividends analysis are pooled cross-sections of annual observations. The data can tell us the probability of any country with a given median age in a given year achieving one of the dividends or not. The model does not predict specific country trajectories, or the timing of transitions from one status to another based on median age

Key Terms

Median Age: The age that divides a population into two numerically equal groups where half the people are younger than this age and half are older.

Total Fertility Rate: The average number of children a woman would have assuming that current age-specific birth rates remain constant throughout her childbearing years (usually considered to be ages 15 to 49).

Design and Production

Jessica Woodin, digital designer

Pamela Mathieson, video and digital producer

N’Namdi Washington, video editor and motion graphics designer

Sizeable Interactive and Prographics, web development partners

Acknowledgments

This interactive web feature was produced in 2017 by Jessica Kali and Elizabeth Leahy Madsen at the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) based on analysis conducted by Richard Cincotta. Special thanks to Shelley Snyder and Apoorva Jadhav, of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), for their time and comments. Updates in 2021 were led by Charlotte Greenbaum, Alex Reed, Kaitlyn Patierno, and Haley Brahmbhatt at PRB, with support from Deborah Bitire, Richard Cincotta, and Elizabeth Leahy Madsen. Updates in 2022 were led by Charlotte Greenbaum, Alex Reed, and Haley Brahmbhatt, and incorporate analysis by Bamikale Feyisetan and Baker Maggwa of USAID on the USAID country roadmaps.

This interactive web feature is made possible by the generous support of USAID under cooperative agreement AID-AA-A-16-00002. The information provided in this document is the responsibility of PRB, is not official U.S. government information, and does not necessarily reflect the views or positions of USAID or the U.S. Government.

References

David E. Bloom, David Canning, and Jaypee Sevilla, The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2003).

Thomas W. Pullum and Apoorva Jadhav, A Decomposition of Sources of Change in Population Size and Median Age, 1970–2020. DHS Working Papers No. 178 (Rockville, MD,: ICF, 2021).

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, “What Can Demography Tell Us About the Advent of Democracy?” New Security Beat (April 28, 2014): https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2014/04/demography-democracy/.

Richard P. Cincotta, Robert Engelman, and Daniele Anastasion, The Security Demographic: Population and Civil Conflict After the Cold War (Washington, DC: Population Action International, 2003).

Richard P. Cincotta and Elizabeth Leahy, “Population Age Structure and Its Relation to Civil Conflict: A Graphic Metric,” www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/population-age-structure-and-its-relation-to-civil-conflict-graphic-metric.

Richard P. Cincotta and Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, “The Four Dividends: The Age-Structural Timing of Transitions in Child Survival, Education Attainment, and Political Stability,” 2017, Paper presented at the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population International Population Conference, Cape Town, South Africa.

Michael Coppedge et al., 2021, “V-Dem Dataset v11.1,” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem): Global Standards, Local Knowledge, https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds21; and Daniel Pemstein et al., 2021. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data,” V-Dem Working Paper No. 21. 6th edition, University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Jacqueline E. Darroch et al., Adding It Up: The Costs and Benefits of Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health 2017 (New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

Mohammad Reza Farzanegan and Stefan Witthuhn. “Demographic Transition and Political Stability: Does Corruption Matter?” Center for Economic Studies & Ifo Institute Working Paper No. 5133.

Jack A Goldstone, “Africa 2050: Demographic Truth and Consequences,” Hoover Institution, Governance in An Emerging World Winter Series, 119 (2019).

Jack A Goldstone, “Population and Security: How Demographic Change Can Lead to Violent Conflict,” Journal of International Affairs 56, no. 1 (2002): 3-22.

Jay Gribble and Jason Bremner, The Challenge of Attaining the Demographic Dividend, 2012, www.prb.org/pdf12/demographic-dividend.pdf.

Daniel Hart et al., “Youth Bulges in Communities: The Effects of Age Structure on Adolescent Civic Knowledge and Civic Participation,” Psychological Science 15, no. 9 (2004): 591-7.

Shareen Joshi, Reproductive Health and Economic Development: What Connections Should We Focus On? (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2012), prb.org/resources/reproductive-health-and-economic-development-what-connections-should-we-focus-on

Ellen Starbird, Maureen Norton, and Rachel Marcus, “Investing in Family Planning: Key to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals,” Global Health Science and Practice 4, no. 2 (2016): 191-210.

John Stover and John Ross, “How Increased Contraceptive Use Has Reduced Maternal Mortality,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 14 (2010): 687-95.

UNESCO, Unpacking Sustainable Development Goal 4 Education 2030, 2016, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002463/246300E.pdf.

United Nations General Assembly, “Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” sustainable development-un.org-transforming our world.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID), FY 2021 USAID Journey to Self-Reliance Country Roadmap Methodology Guide, (Washington, DC: USAID, 2020).

Henrik Urdal, “A Clash of Generations? Youth Bulges and Political Violence,” 2011,www.un.org/esa/population/meetings/egm-adolescents/p10_urdal.pdf.

Hannes Weber, “Demography and Democracy: The Impact of Youth Cohort Size on Democratic Stability in the World,” Democratization 20, no. 2 (2013): 335-57.

WHO, “Newborns: Improving Survival and Well-Being,” www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality.

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, and United Nations Population Division, Maternal Mortality: Levels and Trends 2000 to 2017 (New York: WHO, 2018).

Danzen You et al., Levels and Trends in Child Mortality, 2015, www.unicef.org/media/files/IGME_Report_Final2.pdf.